Custom Embroidery

| Scroll all the way down for pricing |

|

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Machine embroidery is a term that can be used to describe two different actions. The first is using a sewing machine to "manually" create (either freehand or with built-in stitches) a design on a piece of fabric or other similar item. The second is to use a specially designed embroidery or sewing-embroidery machine to automatically create a design from a pre-made pattern that is input into the machine. Most embroidery machines used by professionals and hobbiests today are driven by computers that read digitized embroidery files created by special software.

With the advent of computerized machine embroidery, the main use of manual machine embroidery is in fiber art and quilting projects. While some still use this type of embroidery to embellish garments, with the ease and decreasing cost of computerized embroidery machine, it is rapidly falling out of favor. Many quilters and fabric artists now use a process called "thread drawing" (or thread painting) to create embellishments on items.

Contents |

History

Before computers were affordable, most embroidery was completed by "punching" designs on paper tape that then ran through a mechanical embroidery machine. One error could ruin an entire design, forcing the creator to start over. This is how the term "punching" came to be used in relation to digitizing embroidery designs.

In 1980, Wilcom introduced the first computer graphics embroidery design system running on a mini-computer. The operator would "digitize" the design into the computer using similar techniques to "punching", and the machine would stitch out the digitized design. Wilcom enhanced this technology in 1982 with the introduction of the first multi-user system that allowed more than one person to be working on a different part of the embroidery process, vastly streamlining production times.

Until very recently, high quality computerized embroidery has been out of reach for the casual hobbiest. However, as costs have fallen for computers, software, and embroidery machines, computerized machine embroidery has rapidly grown in popularity since the late 1990s. As of 2006, the average user can buy a machine and special digitizing program to create their own designs for less than $500. Many machine manufacturers sell their own lines of embroidery patterns for those who don't want to create their own. In addition, many individuals and independent companies also sell embroidery designs, and there are thousands of free designs available on the internet.

The Computerized Machine Embroidery Process

These are the basic steps for creating embroidery with a computerized embroidery machine.

- purchase or create a digitized embroidery design file

- edit the design and/or combine with other designs (optional)

- load the final design file into the embroidery machine

- stabilize the fabric and place it in the machine

- start and monitor the embroidery machine

Design Files

Digitized embroidery design files can be either purchased or created. Many machine embroidery designs can be downloaded from web sites and one can be sewing them out within minutes. If design files are to be created, special software is needed to digitize the design (see below). Software vendors often advertise "auto-punching" or "auto-digitizing" capabilities. However, if high quality embroidery is essential, then industry experts highly recommend either purchasing solid designs from reputable digitizers or obtaining training on solid digitization techniques.

Editing Designs

Once a design has been digitized, it can be edited or combined with other designs by software. With most embroidery software the user can rotate, scale, move, stretch, distort, split, crop, or duplicate the design in an endless pattern. Most software allows the user to add text quickly and easily. Often the colors of the design can be changed, made monochrome, or re-sorted. More sophisticated packages will allow the user to edit, add or remove individual stitches. For those without editing software, some embroidery machines have rudimentary design editing features built in.

Loading the Design

After editing the final design, the design file is loaded into the embroidery machine. Different machines expect different files formats. The most common home design format is PES, which works in Brother, BabyLock, some Bernina, White, and Simplicity embroidery machines. Common design file formats for the home and hobby market include: ART, PES, VIP, JEF, SEW, and HUS. The commercial format DST (Tajima) is also very popular. While there are commercial programs to view and convert these files, a simple open source application named Embroidermodder is available for free. Another embroidery design file viewer available free is Wilcom TrueSizer. My favorite free embroidery design file viewer is from Pulse Ambassador the worlds # 1 embroidery software. Here is the link. This software will allow you to view your digitized files. Embroidery patterns can be transferred to the computerized embroidery machines in a variety of ways, either through cables, CDs, floppy disks, USB interfaces, or special cards that resemble flash and compact cards.

Stabilizing the Fabric

To prevent wrinkles and other problems, the fabric must be stabilized. The method of stabilizing depends to a large degree on the type of machine, the fabric type, and the design density. For example, knits and large designs typically require firm stabilization. There are many methods for stabilizing fabric, but most often one or more additional pieces of material called "stabilizers" or "interfacing" are added beneath and/or on top of the fabric. Many types of stabilizers exist, including cut-away, tear-away, vinyl, nylon, water-soluble, heat-n-gone, adhesive, open mesh, and combinations of these. These stablizers are often called Pelan.

For smaller embroidered items, the item to be embroidered is hooped, and the hoop is attached to the machine. There is a mechanism on the machine (usually called an arm) that then moves the hoop under the needle.

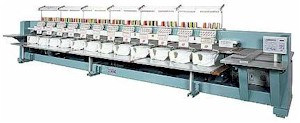

For large commercially embroidered items, a bolt of fabric can be worked by a long row of embroidery "heads", producing a continuous pattern of embroidery. Each embroidery head is a sewing machine with multiple needles for different colors, and is usually capable of producing many special fabric effects including satin-stitch embroidery, chain-stitch embroidery, sequins, applique, cutwork, and other effects. As prices fall, many of the features traditionally available only on professional machines are becoming more affordable in home embroidery machines.

Embroidering the Design

Finally, the embroidery machine is started and monitored. For commercial machines, this process is a lot more automated than for the home embroiderer. For most designs, there is more than one color, and often additional processing for appliques, foam, and other special effects. Since home machines only have one needle, every color change requires the user to cut the thread and change the color manually. In addition, most designs will have a few or many jumps that need to be cut. Depending on the quality and size of the design, stitching out a design file can require a few minutes or an hour or more.

Embroidery Machines

Some machines are for embroidery only. Some machines are a combination of embroidery and sewing. Machines range in price from $200 all the way to more than $125,000 for a large-scale commercial model

just like the ones we use. Here is a

picture of one of our Tajima machines. Most average home embroidery machines can be purchased for less than $1,000. Some of the more advanced features becoming available included a large color touchscreen, a USB interface, design editing software on the machine, embroidery advisor software, and design file storage systems. Commercial embrodiery machines can be purchased as 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 18 head machines.

Some machines are for embroidery only. Some machines are a combination of embroidery and sewing. Machines range in price from $200 all the way to more than $125,000 for a large-scale commercial model

just like the ones we use. Here is a

picture of one of our Tajima machines. Most average home embroidery machines can be purchased for less than $1,000. Some of the more advanced features becoming available included a large color touchscreen, a USB interface, design editing software on the machine, embroidery advisor software, and design file storage systems. Commercial embrodiery machines can be purchased as 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 18 head machines.

Commercial and Contract Embroidery Factories

Factories can have a few small machines or many large machines, depending on what type of orders they are set up for. Some factories run 12 hours a day while others go 24 hours per day. The cost for embroidery is normally based on the stitch count. There is sometimes an extra charge for items that have a difficult logo location or creation.

Editing and Digitizing Software

There are many choices available for software that can organize, print, edit, convert, split, and even digitize new designs. Some websites offer tools that allow you to customize stock designs without the need for expensive digitizing software. Online design tools are generally geared towards the consumer rather than professional. Often the software can be tailored so you pay for only those features you need. If all you want is to embroider a design purchased either from the internet or a reputable digitizer, then you probably don't need any additional software at all.

High quality designs can be created and/or edited by trained users with almost any type of digitizing software, expensive or inexpensive; expensive software simply automates common tasks and complex embroidery techniques. Digitizing and editing software ranges from free to $15,000. For basic software, expect to pay anywhere from a few hundred to a couple thousand. For professional software, expect to pay $5,000 to $15,000 or more, depending on the desired features. While there are some software packages that can auto-digitize artwork, auto-digitized designs usually result in more thread breaks and other problems, and have an arguably lower aesthetic quality relative to designs created by professional human digitizers. It is important to understand that digitizing embroidery from artwork is not the same as using a paint program or a vector-based drawing tool. Fabric and thread have very real limitations with which even art or embroidery professionals need to be familiar. For example, the minimum text size is quite a bit larger than most artists expect, circles need to be digitized as ovals to compensate for fabric pull, and underlay must be chosen properly to support the specific design. Even designs that appear to stitch out correctly may have problems once washed if basic digitizing principles aren't applied. Factors such as the fabric and thread types chosen can profoundly affect the final digitized design.

Fortunately, quality training is finally available. Adorable Ideas, Strawberry Stitch, and Floriani Embroidery are just a few of the companies that provide general training on digitizing. There are also tutorials available for most software packages, though this is usually geared toward their software features rather than on general digitizing techniques. Other good resources include Yahoo groups, books, and a number of magazines on machine embroidery.

These are just a few of the top quality entry level (costing several hundred dollar) editing and digitizing programs: Embroidery Magic 2, Fancyworks Studio, Embird, PE Design/Palette, Origins, and Generations. Manufacturers of professional quality digitizing software include Wilcom, Tajima, Sierra, Barudan, Wings, Compucon, Pulse, Pantograms, and others. Search each of their websites for information on the latest software features and trends.

Other Supplies

Just about any type of fabric can be embroidered, given the proper stabilizer. For example, open lace and fashion scarves can be made in concert with water-soluble stabilizer. New and innovative ways of hooping and embroidering items are being developed. Anything from paper to fabric to lightweight balsa wood and more can be embroidered.

Machine embroidery commonly uses polyester, Rayon, or metallic embroidery thread, though other thread types are available. 40wt thread is the most commonly used embroidery thread weight. Bobbin thread is usually either 60wt or 90wt thread. The quality of thread used can greatly affect the number of thread breaks and other embroidery problems. Polyester thread is generally a higher quality thread that is more color safe and durable. The Superior Threads website is just one excellent resource for information on choosing the proper threads for embroidery.

Other associated costs are thread, stabilizer, purchased designs, needles, bobbins, and other miscellaneous tools and supplies.

Definitions

- Applique

- French term meaning applying one piece of fabric to another. A cut piece of material stitched to another adding dimension, texture and reducing stitch count.

- Backing/Stabilizer

- Materials, generally non-woven textiles, which are placed inside or under the item to be embroidered. The backing provides support and stability to the garment which will allow better results to the finished embroidered product. Backings come primarily in two types: cutaway and tearaway. With cutaway, the excess backing is cut with a pair of scissors. With tearaway, the excess is simply torn away after the item is embroidered. Additional types which are dissolved either by water or heat also exist. For all of these the terms backing and stabilizer are often used interchangeably.

- Bobbin

- A bobbin is a small spool inside of the rotary hook housing. The bobbin thread actually forms the stitches on the underside of the garment. The bobbin on an embroidery machine works in the same manner and for the same purpose as on a home sewing machine.

- Digitize

- To take an image and use an embroidery program to turn it into an embroidery design a computerized machine can read and sew. Often misspelled as "digitalize."

- Fill Stitch

- Fill stitches are series of running stitches formed closely together to form different patterns and stitch directions. Fill stitches are used to cover large areas.

- Running Stitch

- A running stitch is one line of stitches which goes from point A to point B. A running stitch is often used for fine details, outlining, and underlay.

- Satin Stitch

- A satin stitch is a series of zig-zag stitches which are formed closely together. A satin stitch is normally anywhere from 2 mm to 12 mm.

- Underlay

- Underlay stitches are used under the regular stitching in a design. The stitches are placed to provide stability to the fabric and to create different effects. Underlay is normally a series of running stitches or a very light density fill often placed in the opposite direction that the stitching will go.